Una nota excepcional hoy en el New York Times (y también un excelentísimo slide show narrado) sobre la epidemia de influenza del 1918 de los estados unidos. En pocos meses murieron más ciudadanos estadounidenses que soldados yankis en la primera guerra mundial, la segunda guerra mundial, la guerra de Vietnam y la de Corea todas combinadas.

Aparte de narrar los meses horroríficos de muerte, el articulo además especula sobre qué se puede aprender de esa epidemia para pensar y prepáranos para las que vendrán.

Lo escalofriante de estas catástrofes es cuan rápido se propagan. El 28 de Agosto del 1918 en las afueras de Boston, murieron 8 personas de la gripe. El próximo día murieron 58. Dentro de la semana eran 158. Y así hasta que el país estaba inundado en la muerte. La gripe hasta alcanzó a llegar a pueblitos remotos de Alaska al cual sólo se podía llegar por trineo de perros.

Mientras que todo esto sucedía nadie sabía la causa, como frenar las muertes, qué hacer.

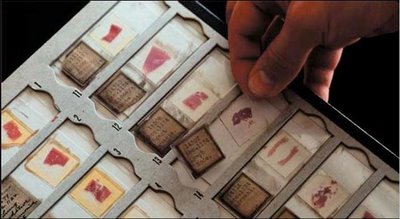

El slide show describe como un doctor actual --Dr. Taubenberger—esta examinando trozos de pulmones que se preservaron de algunas victimas.

También desenterró un cadáver congelado en Alaska de una mujer que murió de la gripe.

Sus conclusiones son desconcertantes. Aunque se esta aprendiendo mucho sobre lo que pasó en 1918, al final no sirve para preparar una estrategia para futuras epidemias.

Ver también una entrevista informativa sobre la gripe aviar actual.

Imagenes: Stills de la presentación multimedia de The New York Times

Futuratrónics cross-index: Here Comes Pandemia!

2 comentarios:

March 28, 2006

The 1918 Flu Killed Millions. Does It Hold Clues for Today?

By GINA KOLATA

Flu researchers know the epidemic of 1918 all too well.

It was the worst infectious disease epidemic ever, killing more Americans in just a few months than died in World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam Wars combined. Unlike most flu strains, which kill predominantly the very old and the very young, this one — a bird flu, as it turns out — struck young adults in their 20's, 30's and 40's, leaving children orphaned and families without wage earners.

So now, as another bird flu spreads across the globe, killing domestic fowl and some wild birds and, ominously, infecting and killing more than 100 people as well, many scientists are looking back to 1918. Did that flu pandemic get started in the same way as this one? Will today's bird flu turn into tomorrow's human pandemic?

And what, if anything, does that nearly century old virus and the pandemic it caused reveal about what is happening today?

The answer is: a lot and not enough. The 1918 pandemic showed how quickly an influenza virus could devastate American towns and cities and how easily it could spread across the globe, even in an era before air travel.

It showed that a flu virus could produce unfamiliar symptoms and could kill in unprecedented ways. And it showed that a bird flu could turn into something that spreads among people.

But the parallels go only so far, researchers say. For now, they are left with as many questions as answers.

In the fall of 1918 flu struck the United States and parts of Europe hard and traveled to every corner of the world except Australia and a few remote islands. A few months later, it vanished, burning itself out after infecting nearly everyone who could be infected.

The virus arrived at even the most improbable places, like isolated Alaskan villages. In one such village, Wales, 178 of its 396 residents died during one week in November, after a mailman arrived by dog sled, bringing the virus along with the mail.

Public health officials tried in vain to contain its spread. In Philadelphia, people were exhorted not to cough, sneeze or spit in public.

But the virus spread anyway. On Oct. 3, Philadelphia closed all of its schools, churches, theaters and pool halls. Still, within a month, nearly 11,000 Philadelphians died of influenza.

Anyone who doubts that flu deaths can be horrific need only read the memoirs of physicians like Dr. Victor C. Vaughan, who treated influenza victims in 1918.

Dr. Vaughan, a former president of the American Medical Association, was summoned by the surgeon general to Camp Devens, near Boston, where the flu struck in September. He later described the scene in his memoirs.

The men, Dr. Vaughan wrote, "are placed on the cots until every bed is full, yet others crowd in."

"Their faces soon wear a bluish cast; a distressing cough brings up the blood stained sputum," he continued.

"In the morning, the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cord wood," Dr. Vaughan said. "This picture was painted on my memory cells at the division hospital, Camp Devens, in the fall of 1918, when the deadly influenza virus demonstrated the inferiority of human inventions in the destruction of human life."

Still, scientists are left with an abiding mystery: Where did the 1918 virus come from?

Investigators know more than they once did. They know exactly what the virus looked like, thanks to Dr. Jeffrey Taubenberger, chief of the division of molecular pathology at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, and his colleagues, who obtained snippets of preserved lung tissue from three victims of the 1918 flu and managed to fish out shards of the virus and piece together its genes. Although the 1918 virus was a strain different from the A (H5N1) virus that is now killing birds, it was, Dr. Taubenberger found, a bird flu.

What is not known is how the 1918 virus moved from birds to humans.

One clue could come from knowing what flu viruses existed before the 1918 pandemic. Perhaps the 1918 virus entered the human population before 1918 in a more benign form then mutated to become a killer. Or perhaps it suddenly showed up in humans, jumping directly from birds to people.

To find out, Dr. Taubenberger and Dr. John Oxford of the Royal London Hospital are looking for human flu viruses that existed before 1918. London Hospital has a collection of human tissue obtained from 1908 to 1918. Dr. Taubenberger is searching for flu viruses in lung tissue from people who died of pneumonia in those years, hoping to use the same methods that allowed him to piece together the 1918 virus to resurrect a flu virus that was in humans before 1918.

The 1918 virus also is teaching researchers about experimental vaccines that scientists hope will protect against a variety of influenza strains. The plan had been to make a sort of universal flu vaccine that would protect against various flu viruses. Then people would not need a flu shot each year, and the vaccine might stop pandemic flu strains from ever gaining a toehold.

But, says Dr. Terrence Tumpey, a microbiologist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, although the experimental vaccines protect against ordinary human flu viruses, they do not protect against the 1918 virus. Nor do they protect against today's A(H5N1) bird flu virus.

That leaves scientists with a puzzle. If they are worried about a 1918-like flu, they want a universal vaccine to protect against it, and they wonder what makes these bird flus so impervious? At this point, no one knows, Dr. Tumpey says.

Another abiding mystery is that neither the 1918 influenza pandemic nor any other human influenza pandemic began with a flu pandemic that killed birds. And, scientists add, if the 1918 pandemic had begun that way, it would have been noticed. Even if the deaths of wild birds went undetected, the deaths of domestic fowl would have been recorded.

Wild birds are inured to most flu viruses — clouds of the viruses normally infect them, living in their gastrointestinal tracts but causing little or no disease. Sometimes, those flu viruses infect poultry and, while they usually cause little illness, some flu strains can be lethal to fowl and economically devastating to farmers.

That, Dr. Taubenberger says, "has been recognized for 150 years." In the 1920's, scientists even isolated viruses from what they used to call fowl plague and what is now known to be bird flu. They were not the same viruses that infected humans.

The problem is in deciding what all this means.

The history of the 1918 flu can take scientists only so far, Dr. Taubenberger said.

"We don't know how the 1918 pandemic evolved and how the virus emerged into a form that was the finished product," he said. "What we sequenced was a virus that was ready for prime time, not its precursor."

"Ultimately," Dr. Taubenberger said, "the answer to the big question is, We don't know. There is no historical precedent for what is going on today."

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/28/science/28flu.html?pagewanted=print

March 27, 2006

Q&A

How Serious Is the Risk of Avian Flu?

By DENISE GRADY and GINA KOLATA

Over the last year, it has been impossible to watch TV or read a newspaper without encountering dire reports about bird flu and the possibility of a pandemic, a worldwide epidemic. First Asia, then Europe, now Africa: like enemy troops moving into place for an attack, the bird flu virus known as A(H5N1) has been steadily advancing. The latest country to report human cases is Azerbaijan, where five of seven people have died. The virus has not reached the Americas, but it seems only a matter of time before it turns up in birds here.

Even so, a human pandemic caused by A(H5N1) is by no means inevitable. Many researchers doubt it will ever happen. The virus does not infect people easily, and those who do contract it almost never spread it to other humans. Bird flu is what the name implies: mostly an avian disease. It has infected tens of millions of birds but fewer than 200 people, and nearly all of them have caught it from birds.

But when A(H5N1) does get into people, it can be deadly. It has killed more than half of its known human victims—an extraordinarily high rate. Equally alarming is that many who died were healthy, not the frail or sickly types of patients usually thought to be at risk of death from influenza.

The apparent lethality of A(H5N1), combined with its inexorable spread, are what have made scientists take it seriously. Concern also heightened with the recent discovery that the 1918 flu pandemic was apparently caused by a bird flu that jumped directly into humans.

In addition, A(H5N1) belongs to a group of influenza viruses known as Type A, which are the only ones that have caused pandemics. All those viruses were originally bird flus. And given the timing of the past pandemics — 1918, 1957, 1968 — some researchers think the world is overdue for another. It could be any Type A, but right now (A)H5N1 is the most obvious.

The virus lacks just one trait that could turn it into a pandemic: transmissibility, the ability to spread easily from person to person. If the virus acquires that ability, a pandemic could erupt.

Everything hangs on transmissibility. But it is impossible to predict whether A(H5N1) will become contagious among people. The virus has been changing genetically, and researchers fear that changes could make it more transmissible, or that A(H5N1) could mix with a human flu virus in a person, swap genetic material and come out contagious.

But most bird flu viruses do not jump species to people. Some experts say that since A(H5N1) has been around for at least 10 years and the shift has not occurred, it is unlikely to happen. Others refuse to take that bet.

The A(H5N1) strains circulating now are quite different from the A(H5N1) strain detected in Hong Kong in 1997, which killed 6 of 18 human victims. Over time, A(H5N1) seems to have developed the ability to infect more and more species of birds, and has found its way into mammals—specifically, cats that have eaten infected birds.

The actual number of human cases may well exceed the number that have been reported, and may include mild cases from which victims recovered without even seeing a doctor. If that is true, the real death rate could be lower. But no one knows whether mild cases occur, or whether some people are immune to the virus and never get sick at all.

In the absence of more information, health officials must act on what they see — an illness that apparently kills half its victims.

Q. How will we know if the virus starts spreading from person to person and becomes a pandemic?

A. If there is a pandemic, it would be everywhere, not in just one city or one country. To detect such an event as early as possible there is an international surveillance system, involving more than 150 countries, that searches for signs that a new flu strain is taking hold in humans. One hallmark of a pandemic flu would be an unusual pattern of illnesses — lots of cases, possibly cases that are more severe than normal and, possibly, flu infections outside the normal flu season.

Ordinary human flu viruses, for reasons that are not entirely understood, circulate only in winter. But pandemics can occur at any time. A pandemic would also involve a flu virus that was new to humans, meaning that no one would have immunity from previous infections.

Q. If bird flu reaches the United States, where is it likely to show up first?

A. Although health officials expect bird flu to reach the United States, it is impossible to predict where it may show up first, in part because there are several routes it could take. If it is carried by migrating birds, then it may appear first in Alaska or elsewhere along the West Coast.

But if the virus lurks in a bird being smuggled into the United States as part of the illegal trade in exotic birds, it could land in any international airport. Bird smuggling is a genuine problem: in 2004, a man was caught at an airport in Belgium illegally transporting eagles from Thailand, stuffed into tubes in his carry-on luggage. The birds turned out to be infected with A(H5N1), and they and several hundred other birds in a quarantine area at the airport had to be destroyed.

In theory, an infected human could also bring bird flu into the United States, and that person could fly into just about any international airport and go unnoticed if the virus had yet to produce any symptoms.

Q. Does bird flu affect all birds?

A. No one knows the full story. Scientists say A(H5N1) is unusual because it can infect and kill a wide variety of birds, unlike a vast majority of bird flus, which are usually found in wild birds, not domestic fowl, and which cause few symptoms.

Some researchers suspect that wild ducks, or perhaps other wild birds, are impervious to A(H5N1), and may be the Typhoid Marys of bird flu — getting the virus, spreading it to other birds but never becoming ill themselves. No one has good evidence of this yet, but that may be because the way scientists discovered A(H5N1) infections was by finding birds that had gotten the flu and died.

As virologists like to point out, dead birds don't fly. So migratory birds cannot spread the virus if they are dying shortly after being infected. That is why some researchers say that if wild birds are spreading the A(H5N1) virus, it must be a bird species that can be infected but does not become ill.

Q. When people die from avian flu contracted from birds, what kills them?

A. Like victims of severe pneumonia, many patients die because their lungs give out. The disease usually starts with a fever, fatigue, headache and aches and pains, like a typical case of the flu. But within a few days it can turn into pneumonia, and the patients' lungs are damaged and fill with fluid.

In a few cases, children infected with A(H5N1) died of encephalitis, apparently because the virus attacked the brain. A number of people have also had severe diarrhea — not usually a flu symptom — meaning that this virus may attack the intestines as well. Studies in cats suggest that in mammals the virus attacks other organs, too, including the heart, liver and adrenal glands.

But more detailed information about deaths in people is not available because very few autopsies have been done. In some countries, like Vietnam, where many of the deaths occurred, autopsies are frowned upon. Researchers say they may glean useful information from autopsies, but fear that pressing for them would alienate the public in some areas.

Q. When experts refer to bird flu as A(H5N1), what does that mean?

Click here to see the answer.

Q. If I got bird flu, how would I know?

A. There is no reason to suspect the disease unless you may have been exposed to it. Since the virus has not reached North America, doctors do not look for bird flu in people unless they have traveled to affected regions or have been exposed to sick or dead birds.

The early stages of the illness in people are the same as those of ordinary flu: fever, headache, fatigue, aches and pains. But within a few days, people with bird flu often start getting worse instead of better; difficulty breathing is what takes many to the hospital.

In any case, patients with flulike symptoms that turn severe or involve breathing trouble are in urgent need of medical care.

Q. Can I be tested for avian flu?

A. There is no rapid test for bird flu. There is a rapid test for Type A influenza viruses, the group that A(H5N1) belongs to, but the test is only moderately reliable, and it is not specific for A(H5N1).

State health departments and some research laboratories can perform genetic testing for A(H5N1) and give results within a few hours, but they do not have the capacity to perform widespread testing.

Because of the limited availability of testing and the extremely low probability of A(H5N1) in people in the United States, the test is recommended only for patients strongly suspected of having bird flu, like travelers with flulike symptoms who were exposed to infected birds.

Q. Do any medicines treat or prevent bird flu?

A. Two prescription drugs, Tamiflu and Relenza, may reduce the severity of the disease if they are taken within a day or two after the symptoms begin. But Relenza, a powder that must be inhaled, can irritate the lungs and is not recommended for people with asthma or other chronic lung diseases.

Both drugs work by blocking an enzyme — neuraminidase, the "N" part of A(H5N1) — that the virus needs to escape from one cell to infect another. But just how effective these medicines are against A(H5N1) is not known, nor is it clear whether the usual doses are enough. Also unknown is whether the drugs will help if taken later in the course of the disease. Although government laboratories and other research groups are trying to develop vaccines to prevent A(H5N1) disease in people, none are available yet.

Q. If there is an epidemic of flu in humans, how can I protect myself?

A. If there is a vaccine available, that would be the best option. But if there is no vaccine it may be hard to avoid being infected. Flu pandemics spread quickly, even to isolated regions. The 1918 flu reached Alaskan villages where the only way visitors could arrive was by dog sled.

The vaccines produced every year to prevent seasonal flu are unlikely to be of any use in warding off a pandemic strain. But a flu shot could provide at least some peace of mind, by preventing the false alarm that could come from catching a case of garden-variety flu.

Similarly, people over 65 and others with chronic health problems should consult their doctors about whether they should be vaccinated against pneumococcal pneumonia, a dangerous illness that can set in on top of the flu. Again, that vaccine will not stop bird flu, but it may prevent complications.

Some health officials have recommended stockpiling two to three months’ worth of food, fuel and water in case a pandemic interferes with food distribution or staffing levels at public utilities, or people are advised to stay home.

Many health experts have advised against stockpiling Tamiflu or Relenza, the prescription-only antiviral drugs that may work against bird flu. Doctors say the drugs are in short supply and hoarding may keep them out of reach of people who genuinely need them.

Also, they say, self-prescribing may lead to waste of the drugs or misuses that spur the growth of drug-resistant viruses. But people may not trust the government to distribute these drugs, and may want their own supplies. Doctors say people can take precautions like avoiding crowds, washing their hands frequently and staying away from those who are sick. Masks may help, but only if they are a type called N-95, which has to be carefully fitted. So far, masks and gloves have been recommended only for people taking care of sick patients.

Avoiding the flu can be hard because it is not always possible to spot carriers. Many people get and spread flu viruses and but never know they are infected.

Q. Is the government prepared for a bird flu pandemic?

A. No. The nation does not have an approved flu vaccine for people or enough antiviral drugs or respirators for all who would need them. The best protection in any flu pandemic will come from a vaccine, but scientists cannot tell ahead of time what strain the vaccine should protect against.

Efforts are under way to make a vaccine for A(H5N1). But the virus could mutate in a way that makes experimental vaccines ineffective, requiring more than one vaccine.

Moreover, there is no assurance that the next pandemic will even involve A(H5N1). It may involve a different strain of bird flu, and an A(H5N1) vaccine would not work for it. Recent efforts to develop a sort of universal flu vaccine that would work across strains have failed.

For now, the hope is to spot a pandemic early and quickly make a vaccine. Investigators are developing new and better ways to make vaccines — a bird flu, for example, cannot be grown in fertilized eggs like other flu viruses because it kills the chicken embryos — but these new methods must first be approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Preparations also include government plans to stockpile drugs to protect people who were exposed to the flu and to reduce the severity of the disease in those who are ill. But the one antiviral drug that everyone wants to buy and stockpile, Oseltamivir, also sold by Roche as Tamiflu, is in short supply.

In retrospect, scientists say, maybe the nation should have started preparing sooner. But until the current bird flu appeared, there was little interest in such expensive and extensive preparations.

Graphic: Stockpiling Drugs

Q. If bird flu reaches the United States, will it be safe to eat poultry or to be around birds or other animals?

A. Poultry is safe to eat when it is cooked thoroughly, meaning that the meat is no longer pink and has reached a temperature of 180 degrees Fahrenheit. The risk is not from cooked meat — cooking kills viruses. Instead, it is from infected birds that are still alive or have recently died. So the person who killed an infected chicken, butchered it or put it in the pot would be at greater risk than the one who ate it.

It's not clear how long the virus lives on a dead bird, but it is unlikely to survive more than a couple of days. And it seems unlikely that infected chicken will find its way to supermarkets.

If the bird flu strikes poultry farms, the farmers will know there is a problem. Before they die, the birds develop major hemorrhages, with blood streaming from their cloacas and beaks. When the flu gets to a poultry farm, farmers have to destroy their flocks, and poulgreater risk than the one who ate it.

As for contact with healthy birds or animals, there is no need to panic. The A(H5N1) virus is a nasty one. If chickens or other animals became infected they would get sick and die, and you would know the virus was present.

But animals can carry many diseases besides influenza, and whenever you are around animals it is a good idea to wash your hands afterward. Because cats in Europe have caught A(H5N1), apparently from eating infected birds, health officials there advise keeping pet cats indoors, but no such recommendation has been made in the United States.

For now, officials at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention say it is safe to have bird feeders, and they note that even if the virus does arrive here, the kinds of birds that perch at feeders are far less likely to carry A(H5N1) than are aquatic birds like ducks and geese.

Q. Is it safe to buy imported feather pillows, down coats or comforters and clothing or jewelry with feathers?

A. Imported feathers may not be safe. There is a risk to handling products made with feathers from countries with outbreaks of bird flu, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Feathers from those countries are banned in the United States unless they have been processed to destroy viruses.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/03/27/health/28qna.html?pagewanted=print

Publicar un comentario