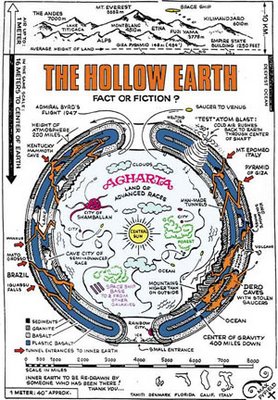

Una de las teorías de conspiración más lindas y antiguas del mundo es que la tierra es hueca. Para ver la abundancia de debate que genera este tema vayan a buscar Hollow Earth en Google.

Para hacerla cosa más interesante y descabellada aun, hay dos variantes de la teoría. Una dice que nuestro plantea es hueco y dentro hay una civilización. La segunda dice que NOSOTROS ESTAMOS ADENTRO de un planeta hueco.

Hoy el Internacional Herald Tribune publica una nota de Umberto Eco repasando la teoría.

Lejos de ser una preocupación de psicópatas uno los defensores fue el astronomo Edmund Halley (1656-1742).

Pero, obviamente, también es una teoría atractiva para los psicópatas. El cabrón de Adolf mandó una expedición Nazi a la isla de los Balcanes Rügen para investigar el tema.

Nos reímos de lo absurdo que parece esta teoría, pero se reian de la misma forma hace poco cuando se declaraba que el planeta daba vuelta al sol, que era redondo, que venimos de los monos, etcétera, etcétera, etcétera…

Como dice mi amigo Hamlet, “There are more things in heavan and earth that are dreamt of in your philosophy.”

24.7.06

¡El mundo es hueco!

Publicadas por

Andrés Hax

a la/s

7/24/2006

![]()

Etiquetas: conspiración

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios de la entrada (Atom)

1 comentario:

Outlandish theories: Kings of the (hollow) world

Umberto Eco The New York Times

Published: July 21, 2006

MILAN There are two Hollow Earth theories. According to the first one we live on the crust, but there is another world on the inside where lies, some say, the realm of Agartha, the home of the King of the World (see, for example, the fantasies of French philosopher René Guénon).

The second theory has it that while we think we live on the outer crust, we actually live in the interior (on a convex surface instead of a concave one).

One of the first Hollow Earth theories was proposed in 1692 by English astronomer Edmund Halley (he who discovered the comet), who suggested that the Earth was composed of four spheres, each embedded in the other like so many matrioshka dolls, illuminated by a luminous atmosphere and perhaps inhabitable.

The theory was reproposed in the early 19th century by J. Cleves Symmes of Ohio, who wrote to various scientific societies: "To all the world: I declare that the Earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one inside the other, and that it is open at the poles 12 or 16 degrees."

Symmes believed that at the North and South Poles there were two apertures that led to the interior of the globe. He attempted to raise funds for an exploration of the polar regions to locate these entrances. The Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences still has a wooden model he used to explain his theories.

The idea was later championed by Jeremiah Reynolds, a newspaper editor, who took it upon himself to promote the expedition at the expense of the American government (a request ultimately denied). The journey was unsuccessful, since he and his party were thwarted by Antarctic ice. At the end of the century the theory was revisited by cult leader Cyrus Reed Teed, who said that what we believe is the sky is a gaseous mass that fills the interior of the globe with areas of bright light (sun, moon and stars would not be heavenly bodies but visual effects).

It is widely rumored on the Internet that the Hollow Earth theory was taken seriously by top-ranking Nazis who believed in the occult sciences. In some circles of the German navy it was purportedly believed that the Hollow Earth theory would make it easier to pinpoint the exact position of British ships because, if infrared rays were used, the curvature of the Earth would not have obscured observation.

Hitler allegedly sent an expedition to the Baltic island of Rügen where a Dr. Heinz Fischer trained a telescopic camera toward the sky in order to spot the British fleet sailing on the interior of the convex surface of the hollow Earth. It is even said that some V1 missile shots went astray because their trajectory was calculated on the basis of a hypothetical concave surface instead of a convex one.

Symmes's story is told well in "Banvard's Folly" by writer Paul Collins, who has reconstructed the stories of a series of madmen. Some were geniuses in their way, scientists who staked their entire careers on false hypotheses. He discusses the lives of men such as respected French physicist René Blondlot, who discovered N-rays in the early 20th century. N- rays didn't exist, but they threw the scientific community of the day into turmoil.

Or consider American artist and showman John Banvard, whose life, Collins says, was "the most perfect crystallization of loss imaginable." In the mid- 19th century he was the richest and most famous painter in the world because of his incredible landscape dioramas, but of both man and his works virtually nothing remains today.

Then there was the forger (and writer) William Ireland, considered stupid by all, even his own father, but who duped all of 18th century England into believing that he had discovered texts, documents and entire works by Shakespeare.

The list continues all the way to music instructor Jean-François Sudre, the inventor and promoter of Solresol, a universal language based solely on musical notes and accessible even to the blind and mute. But Sudre is still remembered in histories of artificial languages, whereas the accomplishments of most of these men - some considered brilliant inventors, famous in their day - eventually sank into oblivion.

On various occasions I have written about "literary madmen," but they are not merely a fixation of mine. I find that reflecting upon outlandish theories that were taken seriously for a long time teaches one to distrust many ideas that are accorded full credence in the media, and even in some scientific circles.

If you search the Internet for "hollow Earth," you'll find that both theories - the one that says we live in the interior of the planet and the one that claims that we live on its exterior, with an entire civilization underneath our feet - still have plenty of adherents.

Or, if you pass a few pleasant hours with Collins's book, at the same time you'll be reminded not to put your faith in the extravagant claims of madmen.

Umberto Eco's most recent novel is "The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loana." This article was translated from the Italian by Alastair McEwen.

MILAN There are two Hollow Earth theories. According to the first one we live on the crust, but there is another world on the inside where lies, some say, the realm of Agartha, the home of the King of the World (see, for example, the fantasies of French philosopher René Guénon).

The second theory has it that while we think we live on the outer crust, we actually live in the interior (on a convex surface instead of a concave one).

One of the first Hollow Earth theories was proposed in 1692 by English astronomer Edmund Halley (he who discovered the comet), who suggested that the Earth was composed of four spheres, each embedded in the other like so many matrioshka dolls, illuminated by a luminous atmosphere and perhaps inhabitable.

The theory was reproposed in the early 19th century by J. Cleves Symmes of Ohio, who wrote to various scientific societies: "To all the world: I declare that the Earth is hollow and habitable within; containing a number of solid concentric spheres, one inside the other, and that it is open at the poles 12 or 16 degrees."

Symmes believed that at the North and South Poles there were two apertures that led to the interior of the globe. He attempted to raise funds for an exploration of the polar regions to locate these entrances. The Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences still has a wooden model he used to explain his theories.

The idea was later championed by Jeremiah Reynolds, a newspaper editor, who took it upon himself to promote the expedition at the expense of the American government (a request ultimately denied). The journey was unsuccessful, since he and his party were thwarted by Antarctic ice. At the end of the century the theory was revisited by cult leader Cyrus Reed Teed, who said that what we believe is the sky is a gaseous mass that fills the interior of the globe with areas of bright light (sun, moon and stars would not be heavenly bodies but visual effects).

It is widely rumored on the Internet that the Hollow Earth theory was taken seriously by top-ranking Nazis who believed in the occult sciences. In some circles of the German navy it was purportedly believed that the Hollow Earth theory would make it easier to pinpoint the exact position of British ships because, if infrared rays were used, the curvature of the Earth would not have obscured observation.

Hitler allegedly sent an expedition to the Baltic island of Rügen where a Dr. Heinz Fischer trained a telescopic camera toward the sky in order to spot the British fleet sailing on the interior of the convex surface of the hollow Earth. It is even said that some V1 missile shots went astray because their trajectory was calculated on the basis of a hypothetical concave surface instead of a convex one.

Symmes's story is told well in "Banvard's Folly" by writer Paul Collins, who has reconstructed the stories of a series of madmen. Some were geniuses in their way, scientists who staked their entire careers on false hypotheses. He discusses the lives of men such as respected French physicist René Blondlot, who discovered N-rays in the early 20th century. N- rays didn't exist, but they threw the scientific community of the day into turmoil.

Or consider American artist and showman John Banvard, whose life, Collins says, was "the most perfect crystallization of loss imaginable." In the mid- 19th century he was the richest and most famous painter in the world because of his incredible landscape dioramas, but of both man and his works virtually nothing remains today.

Then there was the forger (and writer) William Ireland, considered stupid by all, even his own father, but who duped all of 18th century England into believing that he had discovered texts, documents and entire works by Shakespeare.

The list continues all the way to music instructor Jean-François Sudre, the inventor and promoter of Solresol, a universal language based solely on musical notes and accessible even to the blind and mute. But Sudre is still remembered in histories of artificial languages, whereas the accomplishments of most of these men - some considered brilliant inventors, famous in their day - eventually sank into oblivion.

On various occasions I have written about "literary madmen," but they are not merely a fixation of mine. I find that reflecting upon outlandish theories that were taken seriously for a long time teaches one to distrust many ideas that are accorded full credence in the media, and even in some scientific circles.

If you search the Internet for "hollow Earth," you'll find that both theories - the one that says we live in the interior of the planet and the one that claims that we live on its exterior, with an entire civilization underneath our feet - still have plenty of adherents.

Or, if you pass a few pleasant hours with Collins's book, at the same time you'll be reminded not to put your faith in the extravagant claims

http://iht.com/articles/2006/07/21/opinion/edeco.php

Publicar un comentario