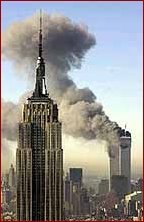

El New York Times reporta hoy que La ciudad de Nueva York hizo publico los audios de 130 llamadas hechas desde las torres el 11 de Septiembre del 2001. Los contenidos estan en 11 compact disc.

El New York Times reporta hoy que La ciudad de Nueva York hizo publico los audios de 130 llamadas hechas desde las torres el 11 de Septiembre del 2001. Los contenidos estan en 11 compact disc.

Acá se pueden escuchar porciones de las llamadas (se oye solamente las operadoras. Dicen que es para proteger la privacidad del muerto) Es tan, tan desesperantemente triste.

Hallways are blocked on 104. Send help to 84. It is hard to breathe on 97.

Be calm, the operators implore. God is there. Sit tight

(Los pasillos estan bloqueados en el 104. Manden ayuda al 84. Es dificil respirar en el 97.

Mantengan la calma, imploran los operadores. Dios esta allí. Quedense quietos.")

Espantósamente las cintas revelan que, aunque hubo una orden oficial de evacuar, los operadores de 911 (el telefóno de emergencias en los estados unidos) les dijieron a toda la gente que llamó que se quedarán fijos en sus oficinas (el articulo explica que este es el procedimiento convencional para los incendios en los rascacielos).

Imagen: fuente

Futuratrónics cross-index: Conspiración 9/11, ¡Más Paranoia! ¡Más Conspiración!, Look out. Here it comes..., "Stand by Manhattan..."

31.3.06

"Dios esta allí. Quedense quietos."

Publicadas por

Andrés Hax

a la/s

3/31/2006

![]()

Etiquetas: conspiración, rascacielos

Suscribirse a:

Comentarios de la entrada (Atom)

4 comentarios:

March 31, 2006

In Operators' Voices, Echoes of Calls for Help

By JIM DWYER

The city released partial recordings today of about 130 telephone calls made to 911 after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, stripped of the voices of the people inside the World Trade Center but still evocative of their invisible struggles for life.

Only the 911 operators and fire department dispatchers can be heard on the recordings, their words mapping the calamity in rough, faint echoes of the men and women in the towers who had called them for help.

They describe crowded islands of fleeting survival, on floors far from the crash and even on those that were directly hit: Hallways are blocked on 104. Send help to 84. It is hard to breathe on 97.

Be calm, the operators implore. God is there. Sit tight.

The recordings, contained on 11 compact discs, also document a broken link in the chain of emergency communications.

The voices captured on those discs track the callers as they are passed by telephone from one agency to another, moving through a confederacy of municipal fiefdoms — police, fire, ambulance — but almost never receiving vital instructions to get out of the buildings.

No more than 2 of the 130 callers were told to leave, the tapes reveal, even though unequivocal orders to evacuate the trade center had been given by fire chiefs and police commanders moments after the first plane struck. The city had no procedure for field commanders to share information with the 911 system, a flaw identified by the 9/11 Commission that city officials say has since been fixed.

The tapes show that many callers were not told to leave, but to stay put, the standard advice for high-rise fires. In the north tower, all three of the building's stairways were destroyed at the 92nd floor. But in the south tower, where one stairway remained passable, the recordings include references to perhaps a few hundred people huddled in offices, unaware of the order to leave.

The calls released today bring to life the fatal frustration and confusion experienced by one unidentified man in the complex's south tower, who called at 9:08 a.m., shortly after the second plane struck the building. For the next 11 minutes, as his call was bounced from police operators to fire dispatchers and back again, the 911 system vindicated its reputation as a rickety, dangerous contraption, one that the administration of former Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani tried to overhaul with little success, and one that Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg hopes to improve by spending close to $1 billion.

The voice of the man, who was calling from the offices of Keefe Bruyette on the 88th floor of that building, was removed from the recording by the city. From the operator's responses, it appears that he wanted to leave.

"You cannot — you have to wait until somebody comes there," she tells the man.

The police operator urged him to put wet towels or rags under the door, and said she would connect him to the Fire Department.

As she tried to transfer his call, the phone rang and rang — 15 times, before the police operator gave up and tried a fire department dispatch office in another borough. Eventually, a dispatcher picked up, and he asked the man to repeat the same information that he had provided moments earlier to the police operator. (The police and fire departments had separate computer dispatching systems that were unable to share basic information like the location of an emergency.)

After that, the fire dispatcher hung up, and the man on the 88th floor apparently persisted in asking the police operator — who had stayed on the line — about leaving.

"But I can't tell you to do that, sir," the operator said, who then decided to transfer his call back to the Fire Department. "Let me connect you again. O.K.? Because I really do not want to tell you to do that. I can't tell you to move."

A fire dispatcher picked up and asked — for the third time in the call — for the location of the man on the 88th floor. The dispatcher's instructions were relayed by the police operator.

"O.K.," she said. "I need you to stay in the office. Don't go into the hallway. They're coming upstairs. They are coming. They're trying to get upstairs to you."

Like many other operators that morning, she was invoking advice from a policy known as "defend in place" — meaning that only people just at or above a fire should move, an approach that had long been enshrined in skyscrapers in New York and elsewhere.

At Keefe Bruyette, 67 people died, many of whom had gathered in conference rooms and offices on the 88th and 89th floors. Some tried to reach the roof, a futile trek that the 9/11 Commission said might have been avoided if the city's 911 operators had known that the police had ruled out helicopter rescues — another piece of information that had not been shared with them — and that an evacuation order had been issued.

The calls were released today in response to a Freedom of Information request made by The New York Times on Jan. 25, 2002, for public records concerning the events of Sept. 11. The city refused to release most of them on the grounds that they were needed to prosecute a man accused of complicity in the attacks, or contained opinions that were not subject to disclosure, or were so intensely personal that their release would be an invasion of privacy. The Times sued in state court, and nine family members of people killed in the attacks joined the case.

Judge Richard Braun of the State Supreme Court in Manhattan ruled in early 2003 that the vast majority of the records were public, but said that the city could remove the words of the 911 callers on privacy grounds. Over the next two years, the core of his ruling was affirmed by the appellate division and the New York State Court of Appeals.

That led to the release of the calls today. City officials said that 130 calls were made to 911 from inside the buildings. Of that group, officials were able to identify 27 people and notified their next of kin this week that they could listen to the complete call.

While that might seem like a small number of calls given that approximately 15,000 people were at the trade center that morning, officials said that many of those who got through to 911 were with large groups of people.

One of these groups was on the 105th floor of the south tower, a spot where scores of people had congregated after trying to reach the roof. Among them was Kevin Cosgrove, who worked on the 100th floor, and who had told his family that he had gone down stairs before turning back. He called 911, and said he was in an office overlooking the World Financial Center, across West Street, records show. He said he needed help, and was having difficulty breathing.

One of the recordings — city officials have refused to say who made the call — involved a man on the 105th floor who suggested desperate measures to improve the air.

"Oh, my God," said the dispatcher. "You can't breathe at all?"

The caller's words were deleted.

"O.K.," said the dispatcher. "Listen, when you — listen, please do not break the window. When you break the window — " here, the caller interrupted.

"Don't break the window because there's so much smoke outside," the dispatcher said. "If you break a window, you guys won't be able to breathe; . O.K.? So if there are any other doorways that you can open where you don't see the smoke."

The dispatcher tried to soothe the man, finally saying, "O.K. Listen, calm yourself down. We've got everybody outside. O.K.?"

The man spoke and the dispatcher assured him help was on the way.

"We are," the dispatcher said. "We're trying to get up there, sir. Like you said, the stairs are collapsed. O.K.? Everybody wet the towels and lie on the floor. O.K.? Put the wet towels over your head and lie down; O.K.? I know it's hard to breathe. I know it is."

People on the highest floors in both towers suffered acutely from the smoke and heat, even though they were many floors distant from the entry points of the planes that had crashed into the buildings. In the offices of Cantor Fitzgerald in the north tower, between 25 and 50 people found refuge in a conference room on the 104th floor. One man, Andrew Rosenblum, reached his wife in Long Island, and gave her the names and home phone numbers of colleagues who were with him. As he recited the information, she relayed it to neighbors. Mr. Rosenblum also called a friend and said that the group had used computer terminals to smash windows for fresh air.

Such drastic actions appeared to have been discouraged by the operator. Another Cantor Fitzgerald employee on the 104th floor was Richard Caggiano, who called 911 at 8:53, seven minutes after the plane hit the north tower.

"Don't do that, sir," the operator said. "Don't do that. There's help on the way, sir. Hold on."

Mr. Caggiano's words, which were not made public, prompted a question from the operator.

"Are y'all in a particular room?" she asked. "How many?"

She listened, then said, "25 or 30 in a back room. O.K. They're on the way. They're already there. You can't hear the sirens?"

Just before the south tower collapsed at 9:59 a.m., a spurt of calls reached the 911 operators. One of these was from Shimmy Biegeleisen, who worked for Fiduciary Trust in the south tower on computer systems. He was on the 97th floor where, by chance, an emergency drill had been scheduled for that day. Mr. Biegeleisen called his home in Brooklyn, spoke with his wife and prayed with a friend, Jack Edelman, who remembered hearing him say: "Of David. A Psalm. The earth is the Lord's and all that is in it, the world and those that live in it."

At 9:52, he called 911. The building had seven more minutes before it would collapse. Mr. Biegeleisen would spend those minutes telling first the police operator, then the fire dispatcher, that he was on the 97th floor with six people, that the smoke had gotten heavy.

The police operator tried to encourage Mr. Biegeleisen.

"Heavy smoke. O.K. Sir, please try to keep calm. We'll send somebody up there immediately. Hold on. Stay on the line. I'm contacting E.M.S. Hold on. I'm connecting you to the ambulance service now."

As his call was transferred to the ambulance service, once again, the information about the smoke and the 97th floor was sought and delivered.

"Sir, any smoke over there?" asked the ambulance dispatcher. "O.K. the best thing to do is to keep — keep down on the ground. All right? O.K.?"

The ambulance dispatcher hung up, but the original operator stayed on the line with Mr. Biegeleisen. She could be heard speaking briefly with someone else in the room, and then turned her attention back to him

"We'll disengage. O.K.?" the operator asked. "There were notifications made. We made the notifications. If there's any further, you let us know. You can call back."

Seconds later, the building collapsed.

http://nytimes.com/2006/03/31/nyregion/31cnd-tapes.html?ei=5094&en=7974754cad2d453e&hp=&ex=1143867600&partner=homepage&pagewanted=print

April 1, 2006

Tapes Reveal How Operators Handled 9 / 11

By THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Filed at 10:27 a.m. ET

NEW YORK (AP) -- The instructions to those trapped above where airliners had slammed into the World Trade Center on Sept. 11, 2001, sometimes sounded stern, sometimes sympathetic. But the central theme was the same: Stay put.

''We are trying to get up there, sir. Like you said, the stairs are collapsed, OK?'' a fire dispatcher told one frantic caller trapped on the 105th floor of the south tower. ''I know it's hard to breathe. I know it is.''

The desperate attempts to calm callers' fears amid the chaos were revealed on several hours of 911 tapes released Friday as the result of a lawsuit. In many instances, dispatchers assured the callers on the upper floors that help was coming, or already there.

''OK, ma'am. All right,'' the same fire dispatcher told a caller at 9:05 a.m., two minutes after a plane hit the second tower. ''Well, everybody is there now. We're trying to rescue everybody. OK?''

The tapes show that the dispatchers -- some of them based at a distant facility in Central Park -- struggled to keep pace with the furiously unfolding scene, and were slow to grasp that it was a choreographed terrorist attack involving two planes and both towers.

But emergency officials credited them on Friday with generally keeping their composure, and giving the right advice for high-rise tenants trapped by fires raging on lower floors.

''While today's release of 911 dispatch tapes brings back painful memories, it also clearly demonstrates that our dispatchers were unsung heroes on the darkest day in our city's history,'' Fire Commissioner Nicholas Scoppetta said in statement.

A small group of people who lost loved ones in the terrorist attacks gathered at a Manhattan law office to hear recordings of the 911 calls.

Sally Regenhard, whose son Christian, a firefighter, died in the attacks, said she believed more people would have survived if better information had been available to rescuers.

''I'm hoping that the public and the system will learn how unprepared the City of New York and the Port Authority were on that day,'' she said.

The knowledge that some callers died in the unexpected collapse of the towers severely traumatized those who had repeatedly told them to sit tight. Some dispatchers never came back to work after that day. Some retired early.

''Unfortunately, they took it very much to heart,'' said David Rosenzwieg, a dispatcher supervisor.

The 130 calls edited out the voices of those who sought help after terrorists flew the hijacked jets into the twin towers, but the police and fire dispatchers often repeated the callers' words, reflecting the chaos of the morning of the attack that killed 2,749 people at the trade center.

The voices of the fire and police operators who heard the calls for help were released after The New York Times and relatives of Sept. 11 victims sued to get them. An appeals court ruled last year that the calls of victims in the burning twin towers were too intense and emotional to be released without their families' consent.

The transcripts of the calls held long blank spaces where the callers' words would have appeared. Often, the operators talked to each other about trying, even as their computers crashed, to deal with the once-unimaginable situation.

''All right, we have quite a few calls,'' said a fire operator.

''I know,'' responded a police operator. ''Jesus Christ.''

Sirens screamed in the background as the callers pleaded for help. Although there were no voices, their desperation was evident in heavy, audible breathing on the other line of the operators' calls.

''If you feel like your life is in danger, do what you must do, OK?'' one dispatcher told a caller at 9:02 a.m., just a minute before the second plane hit. ''I can't give you any more advice than that.''

The first transcripts released as part of the Times lawsuit came last August, when thousands of pages of oral histories of firefighters and emergency workers, as well as radio transmissions, were released. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owned the trade center and has its own police force, released all of its emergency recordings in 2003.

The Sept. 11 commission concluded in 2004 that the operators did not have enough information to allow more people to escape. Some took time to even know the towers had fallen.

''Are they still standing?'' one dispatcher asked at 10:15 a.m., 16 minutes after the south tower collapsed. ''The World Trade Center is there, right?''

------

Associated Press writers Frank Eltman, Amy Westfeldt, Nahal Toosi, David B. Caruso and Shaya Tayefe Mohajer contributed to this report.

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/us/AP-Attacks-911-Calls.html?_r=1&oref=slogin&pagewanted=print

April 1, 2006

The Calls

City Releases Tapes of 911 Calls From Sept. 11 Attack

By JIM DWYER

The city released partial recordings yesterday of about 130 telephone calls made to 911 on Sept. 11, stripped of the voices of the people inside the World Trade Center but still evocative of their invisible struggles for life.

Only the 911 operators and Fire Department dispatchers can be heard on the recordings, their words mapping the calamity in rough, faint echoes of the men and women in the towers who had called them for help.

They describe messages from pockets of the buildings that were crowded with people who had survived, even on floors that had been in the direct path of the planes: Hallways are blocked on 104. Send help to 84. It is hard to breathe on 97.

Be calm, the operators implore. Help is on the way. God is there. Sit tight.

The recordings, on 11 compact discs, also document in painful detail a failed link in the chain of emergency communications, which was first cited by the 9/11 Commission.

No more than two of the 130 callers to 911 were told to leave the towers, the tapes reveal, even though unequivocal orders to evacuate the entire trade center had been given about 10 minutes after the first plane hit, by fire and police commanders on the scene. Indeed, most callers were told to wait, the standard advice in ordinary high-rise fires. The city had no procedure for field commanders to share fresh information with the 911 system.

The result, the tapes show, is that as the unseen callers were passed by telephone from one agency to another, moving through a confederacy of municipal fiefs — police, fire, ambulance — they almost never received instructions to get out of the buildings. Instead, operators continued to press many callers to stay put.

On the upper floors of the north tower, good advice probably would not have saved anyone: all three of the building's stairways had been destroyed at the 92nd floor. But some callers from below the 92nd floor were also told to wait for help, and in the south tower, where one stairway remained passable, the recordings include references to perhaps a few hundred people huddled in offices, unaware of the order to leave.

One unidentified man in the south tower called at 9:08 a.m., shortly after the second plane struck the building. For the next 11 minutes, as his call was bounced from police operators to fire dispatchers and back again, the 911 system confirmed its reputation as a rickety, dangerous contraption, one that the administration of Mayor Rudolph W. Giuliani had tried to overhaul with little success, and one that Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg hopes to improve by spending close to $1 billion.

The voice of the man, who was calling from the 88th-floor office of Keefe, Bruyette & Woods, was removed from the recording by the city. From the police operator's responses, it appears he wanted to go. "You cannot. You have to wait until somebody comes there," she says.

The operator urged him to put wet towels or rags under the door and said she would connect him to the Fire Department. As she tried to transfer his call, the phone rang and rang — 15 times, before the police operator gave up and tried a Fire Department dispatch office in another borough. Eventually, a dispatcher picked up, and he asked the man to repeat the information that he had provided moments earlier to the police operator. (The Police and Fire Departments run separate computer dispatching systems that are unable to share basic information.)

After that dispatcher hung up, the man on the 88th floor apparently persisted in asking the police operator, who stayed on the line, about leaving.

"But I can't tell you to do that, sir," said the operator, who then decided to transfer his call back to the Fire Department. "Let me connect you again. O.K.? Because I really do not want to tell you to do that. I can't tell you to move."

A fire dispatcher picked up and asked — for the third time in the call — for the man's location. The dispatcher's instructions were relayed by the police operator.

"O.K.," she said. "I need you to stay in the office. Don't go into the hallway. They're coming upstairs. They are coming."

Like many other operators that morning, she was invoking advice from a policy known as "defend in place" — meaning that only people just at or above a fire should move, an approach that counts on fire being contained to a single floor and flames and smoke rising. The policy has long been enshrined as tactical wisdom for firefighting in skyscrapers in New York and elsewhere.

At Keefe, Bruyette, 67 people died. Many of them had gathered in conference rooms and offices on the 88th and 89th floors. Some tried to reach the roof, a futile trek that the 9/11 Commission said might have been avoided if the 911 operators had known that the police had ruled out helicopter rescues — another piece of information that had not been shared — and that an evacuation order had been issued.

Mayor Bloomberg, whose administration has fought the release of these and other public records about public safety on Sept. 11, was asked this week about the information that 911 operators and dispatchers gave to callers.

"When you have a disaster of this size, I think it is clear that there will be lots of information that later will turn out not to be accurate," he said. "I think the operators did probably as good a job as you could ask for."

Family members and others who had sought the release of the tapes said they did not blame the 911 operators. Glenn Corbett, a professor of fire science at John Jay College and an adviser to a family group called the Skyscraper Safety Campaign, said the operators simply did not have the information they needed.

That was one reason he and others had urged the city to release the entire 911 recordings, not just the operators' portions. "We would see what information was missed that could have been relayed to others and could have saved lives," he said.

The mayor said he was sympathetic to families who had sought the recordings and to those who did not want them released.

"We will do whatever the courts want, but my personal opinion has always been, we should remember those that we lost and not focus on that particular day, or those conversations," Mr. Bloomberg said.

The calls were made public yesterday in response to a Freedom of Information request made by The New York Times on Jan. 25, 2002, for public records concerning the events of Sept. 11.

Aides to Mr. Bloomberg, who was in his first month in office, immediately refused to release most of the records, on the grounds that they were needed to prosecute Zacarias Moussaoui for complicity in the attacks; or contained opinions that were not subject to disclosure; or were too personal. The Times sued, and nine family members of people killed in the attacks joined the case.

Justice Richard F. Braun of State Supreme Court in Manhattan ruled in early 2003 that the vast majority of the records were public, but he said that the city could remove the words of the 911 callers on privacy grounds, a decision upheld by the Court of Appeals one year ago. Last August, the city released 12,000 pages of oral histories and dispatch recordings, but officials said they needed more time to remove the callers' voices from the 911 recordings.

Last week, the officials revealed that they had also cut portions of the operators' remarks, maintaining that such editing was consistent with the "intent" of the Court of Appeals to protect privacy. At the request of The Times, Justice Braun ordered the city on Wednesday to restore the operators' words. The city has appealed.

City officials said about 130 calls were made to 911 from inside the buildings. Of that group, officials were able to identify 27 people and notified next of kin this week that they could listen to the complete call.

Kevin Cosgrove was among scores of people who had gathered on the 105th floor of the south tower after trying, without success, to open doors to the roof. Mr. Cosgrove, who worked on the 100th floor, told his family that he had earlier headed downstairs before turning back. He called 911 and said he was in an office overlooking the World Financial Center, across West Street, records show. He said he needed help and was having difficulty breathing.

One recording from the 105th floor — city officials have refused to name the caller — involved a man who suggested desperate measures to improve the air.

"Oh, my God," said the dispatcher. "You can't breathe at all?"

The caller's words were deleted.

"O.K.," said the dispatcher. "Listen, when you — listen, please do not break the window. When you break the window ——"

Here, the caller interrupted.

"Don't break the window because there's so much smoke outside," the dispatcher said. "If you break a window, you guys won't be able to breathe. O.K.? O.K.? So if there are any other doorways that you can open where you don't see the smoke."

The dispatcher tried to soothe the man, finally saying, "O.K. Listen, calm yourself down. We've got everybody outside; O.K.?"

The man spoke and the dispatcher assured him that help was on the way.

"We are," the dispatcher said. "We're trying to get up there, sir. Like you said, the stairs are collapsed; O.K.? Everybody wet the towels and lie on the floor; O.K.? Put the wet towels over your head and lie down; O.K.? I know it's hard to breathe. I know it is."

In one recording, an operator mentioned that a man had called from the 84th floor of the south tower — the second plane had plowed into the building at that spot — and was with 20 other people just before the building collapsed. In another, an ambulance dispatcher asked, "How could you have a big building like that and no way to get out of it?"

People on the highest floors of both towers suffered acutely from the smoke and heat, even though they were many floors distant from the entry points of the planes that had crashed into the buildings. In the offices of Cantor Fitzgerald in the north tower, 25 to 50 people found refuge in a conference room on the 104th floor.

One man, Andrew Rosenblum, reached his wife in Long Island and gave her the names and home phone numbers of colleagues who were with him. As he recited the information, she relayed it to neighbors. Mr. Rosenblum also called a friend and said the group had used computer terminals to smash windows for fresh air.

Such drastic actions appeared to have been discouraged by operators. Another Cantor Fitzgerald employee on the 104th floor was Richard M. Caggiano, who called 911 at 8:53, seven minutes after the plane hit the north tower.

"Don't do that, sir," the operator said. "Don't do that. There's help on the way, sir. Hold on."

Mr. Caggiano's words, which were not made public, prompted a question from the operator.

"Are y'all in a particular room?" she asked. "How many?"

She listened, then said, "Twenty-five or 30 in a back room. O.K. They're on the way. They're already there. You can't hear the sirens?"

Just before the south tower collapsed at 9:59, a spate of calls reached the 911 operators.

Shimmy D. Biegeleisen, who worked on computer systems for Fiduciary Trust in the south tower, was on the 97th floor, where, by chance, an emergency drill had been scheduled for that day.

He called his home in Brooklyn, spoke with his wife and prayed with a friend, Jack Edelman, who said Mr. Biegeleisen recited the 24th Psalm in Hebrew: "Of David. A Psalm. The earth is the Lord's and all that is in it, the world and those that live in it."

At 9:52, Mr. Biegeleisen called 911. The building would stand for seven more minutes. He spent those minutes telling first the police operator, then the fire dispatcher, that he was on the 97th floor with six people, that the smoke had gotten heavy.

The police operator tried to encourage Mr. Biegeleisen.

"Heavy smoke. O.K. Sir, please try to keep calm. We'll send somebody up there immediately. Hold on. Stay on the line. I'm contacting E.M.S. Hold on. I'm connecting you to the ambulance service now."

As his call was transferred to the ambulance service, once again the information about the smoke and the 97th floor was sought and delivered.

"Sir, any smoke over there?" asked the ambulance dispatcher. "O.K., the best thing to do is to keep — keep down on the ground. All right? O.K.?"

The ambulance dispatcher hung up, but the original operator stayed on the line with Mr. Biegeleisen. She could be heard speaking briefly with someone else in the room, and then turned her attention back to him.

"We'll disengage, O.K.?" the operator asked. "There were notifications made. We made the notifications. If there's any further, you let us know. You can call back."

Seconds later, the building collapsed.

Reporting for this article was contributed by Sewell Chan, Kate Hammer, Samantha H. Storey and Lisa Tozzi.

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/01/nyregion/01tapes.html?pagewanted=print

For 911 Operators, Sept. 11 Went Beyond All Training

By AL BAKER and JAMES GLANZ

The calls had come in without pause, minute after minute. The emergency operators had no time to do anything but give advice and appeal for calm.

Then, about 9:50 that morning, the 911 phone line seemed to have gone dead. It was a rare moment for people near the center of the tragedy to reflect on what was happening, their thoughts recorded as they spoke quietly to each other on the same phones that connected them to the World Trade Center.

"I don't know what they're doing," an Emergency Medical Service operator said. She was referring to a group of perhaps five people she had been talking with on the south tower's 83rd floor before they had gone silent. "And it's an awful thing. It's an awful, awful, awful thing to call somebody and tell them you're going to die.

"That's an awful thing. I hope — I hope they're all alive because they sound like they went — they passed out because they were breathing hard, like snoring, like they're unconscious."

Nine minutes later, the south tower fell, and 29 minutes after that, the north tower went down. The moment for reflection soon passed and the calls began coming again as the final chapters in the tragedy unfolded.

So it went that morning for the people handling the 911 system.

Overworked, overwhelmed, they were thrust into situations for which no training could prepare them. Yet they kept picking up the phones, improvising answers even when they were exasperated, even when they were in the dark about evacuation orders that had been issued by fire and police commanders.

Helplessness increasingly defined their predicament, and it showed in some of their conversations.

"I wish I could tell you," one operator told a caller. "I don't know anything more than what people calling in tell me. I don't have any access to a radio or TV or anything. I don't know. I'm looking at the job and there are people there. I mean everybody's there. Please."

Yesterday, as the tapes of these calls were released, Patrick J. Limage, 30, a dispatcher for the Emergency Medical Service who took 10 or 15 calls from the towers that day, found his thoughts wandering back.

"In my mind I am just picturing how the situation was for these callers," Mr. Limage said. "What were they seeing as they tried to relay this information to me? I'm trying to play it back in my mind; what they were telling me. What were they feeling at the time?"

On a day when all New York seemed under siege, few felt the pressure more than the 911 operators into whose headsets poured the shouts for help. In moments, they were transformed from anonymous voices in the gears of government to something like priests. They were a last human voice for the dying as they juggled a volume and depth of calls unheard of in the city, all transmitted over an antiquated answering system whose designers had not envisioned such a surge.

In transcripts and tapes released by the city yesterday, the operators were not identified by name. But to listen to their voices is to revisit the stark dilemmas of that day, to touch the contrary themes that defined it — dedication and ignorance, professionalism and mistakes — as well as some fleeting moments of humanity that arose as they sought graceful ways to end conversations that were often the final calls of the doomed.

"Take care," they said. "Bless you." "Bye-bye." "Were you able to call your family?" "Hold on."

Inside the towers, flames seared. Smoke thickened. Questions tumbled, one after another. And in the 102 minutes between the time the first plane struck the north tower, at 8:46 a.m., and when that tower fell, at 10:28 a.m., the operators' demeanor often evolved, from the brisk professionalism, gruff efficiency of a worker with two hands and eight calls to answer to the more deliberate sympathies of human beings as the prospects for rescue became more remote.

Details emerged in the operators' conversations with people inside the towers, those calling from the fire zones, and with their colleagues seated next to them or in similar communications bunkers spread through the city as they flipped calls back and forth to one another.

Three types of municipal workers took the calls: police, fire and ambulance dispatchers and operators.

Union officials for the three groups tallied the numbers. About 35 Fire Department dispatchers were on duty that morning in five communications offices positioned in parks (as required by an early 1900's law) in each borough, including the Manhattan command at 79th Street in Central Park.

The Police Department's 911 operators, about 200 strong, were located in Brooklyn and Manhattan. Operators and dispatchers for the Emergency Medical Service, about 50 people, were seated at 1 Metro Tech in Brooklyn.

More than 3,000 calls flooded the 911 system in the first 18 minutes, and more than 57,000 in the 24 hours after the first plane hit the north tower. The calls from inside the towers totaled about 130, though many of those came from people in groups, sometimes of 100 or more.

Like everyone who collided in one way or another against this tragedy, the emergency operators had their own personal journeys to make on this day, states of mind marked by large and small epiphanies. The difference was that the operators had to continue doing their jobs while jousting with the raw reality inside the towers.

At times, the operators seemed overwhelmed. Then, perhaps trying to cut the tragedy down to something familiar, they often fixed on technicalities like which codes should be used to log the calls.

"Oh, that's what I need, another call," an operator said at 9:13. "Do you want to make a new job?" the operator asked, referring to the logging system in the computers. There was squabbling over how to classify the calls. One operator, however, cut his colleague off, telling him not to worry about the category. "The whole thing is a rescue," the operator said.

In answering the callers from the towers, many of them clearly took to heart the message of their training — get the information fast and get off. Another call, another emergency is waiting. The operators became almost cocksure at times, exuding faith in the rescuers

"We will be there shortly," a fire dispatcher, No. 328, told a man who called at 9:02 a.m., presumably from the north tower. "We are in the building."

It was the clipped unemotional language of a worker with too many calls to answer, all of them important. "The address of the fire?" "One World or Two World?" "What floor are you on?"

They were efficient to the point of being abrupt: "I got to answer more calls," a fire dispatcher told a man at 8:51 a.m. "Can you speed it up?"

At 8:58 a.m., a woman reached a fire dispatcher to report a car on fire at Albany and West Streets, just outside the towers. "O.K., have you looked up toward the top of the Trade Center lately?" the dispatcher asked. "That's probably what it's from."

Other times, simple confusion reigned. Were they facing a plane crash, an explosion, a fire? All three? A lack of knowledge about what was happening shone through in some exchanges.

"Do you have any news about it?" one operator asks another. "Like any of the latest?"

"No, nothing later," is the response. "Are they still standing? The World Trade Center is there, right?"

Amid the drama the operators faced a welter of mechanical problems. Computers did "crazy things," phones went down, and they discussed the need to "dupe everything," according to the transcripts. And in the middle of it, the rest of the city called with routine emergencies. At 9:30 a.m. it was a report of a man whose leg had gotten stuck in a revolving door on Lexington Avenue.

Sometimes it got ugly as people involved in other emergencies, overcome with worry, demanded immediate assistance.

"A lot of them were very abusive because they felt they were being ignored," Mr. Limage said. "Some of these people were cursing us out."

And the operators had concerns for themselves: At one point, worried that terrorists might train weapons on their posts, the city's very communications hubs, they called their local police precincts to ask for police officers to come stand sentry at the doors to their buildings.

As the day wore on, they faced impossible decisions to hold the line, or end the call and hear from another terrified soul.

At 9:49 a.m., fire dispatcher 408, identified by his union leader as James Raftery, hung on for almost two minutes with a man stuck on the 105th floor, telling him at least 12 times that help is "coming," it's "on the way." Finally, exasperated, he swore help will come.

"I swear to you," Mr. Raftery said, as the call ended. "I swear to you, we'll get somebody up to you."

Calls came over and over from some of the same spots in the towers where pockets of people had sought shelter, producing fragmentary narratives as conditions worsened. At about 9:14, one operator took a call from the 86th floor in the north tower. "Trapped on the 86th floor," the operator said.

Another call came from the floor 30 minutes later. At least one call before and after those were also logged to fire dispatchers.

"Do you have a phone number to your home that you would like for us to call anybody?" an operator asked in one of the later calls. And then, after one of the exchanges had ended, another operator who had been on the line asked: "I wonder what's taking them so long to get to the 86th floor?"

Repeat calls came from the 105th floor of the north tower, where 60 people had gathered, as well as other floors like the 97th and 83rd floors of the south tower.

Some of the calls for help came not from inside the building, but from suburban police departments who had been called by relatives of those trapped. Even when relatives contacted by people trapped in the towers called local police stations, the calls wound up in the laps of the city's 911 operators.

Some dispatchers and supervisors now feel stricken by any suggestion that lives were lost because they relied on the traditional policy of "defend in place" firefighting, where only those at or above a fire in a high rise building should move.

"When you listen to the tapes, it sounds like we are telling them the wrong thing and in reality we are telling them the right thing," said Judith Salgado, 36, a borough supervisor who worked in the Fire Department's Manhattan command center on Sept. 11. "No one thought those buildings were going to come down."

Mr. Raftery, identified by the head of his union, David Rosenzweig, did not want to speak about his memories of Sept. 11. Mr. Rosenzweig said he was stung by criticism after a tape of him speaking was broadcast Thursday on the news. Lost in it all, however, is any praise for the operators for their commitment, professionalism and control that day, Mr. Rosenzweig said.

The day was so traumatic, some could not return. That was the case for Monsitah Corney, who fielded several calls from those in the towers, Mr. Rosenzweig said. She left the job soon after Sept. 11, never to answer 911 calls again.

For Ivan Goldberg, who was working as deputy director of dispatch operations for the Fire Department that day, working at the Manhattan command center that day, "changed my life forever."

"A lot of dispatchers have retired in the last four years," he said. "For me, the decision to leave the job three months after the incident was hastened by the fact that the Fire Department became a very sad place to work." He paused, and added, "I lost a lot of friends and co-workers and a first cousin."

Mr. Rosenzweig said 135 new dispatchers were trained over 18 months in 2002 and 2003, reflecting the rapid exodus. Mr. Goldberg said that rehashing the day had opened old wounds for many. But he said that, looking back, "they did the best job they could have done, given the circumstances."

It is the haunting voices on the tapes of that day, the earliest historic trace of the unfolding horror, that seem to bear out the truth of Mr. Goldberg's belief in the valor of his colleagues.

As the seconds ticked away and the end came near, sympathy for those near death shone through again and again.

"Stop talking and let the air ..." a fire dispatcher, No. 328, said at 10:17 a.m., to a man on the 97th floor of the north tower. "You're losing your oxygen. So try to be quiet and remain calm. O.K.?"

When the terrible circumstances began to slip beyond human control, the operators sometimes reached further.

"Just hold on one second, sir," a police operator said to a man on the 105th floor. "Hold on. I hear the fire alarm. They're coming. They're on their way. They're working on it. My God, this — don't worry. God is there. God is there. God is — don't worry about it. God is — don't worry."

http://www.nytimes.com/2006/04/01/nyregion/01operator.html?pagewanted=print

Publicar un comentario